Enki rose before dawn. He had taught himself to wake in time to get to his family’s farm before sunrise.

Enki rose before dawn. He had taught himself to wake in time to get to his family’s farm before sunrise.

The position of the stars above him told him that the sun would soon rise. Gu-Anna, the great bull of heaven was low in the sky towards the west.

His parents were still asleep on top of their house, hoping to catch whatever chance breeze might blow through the dusty alleys of Uruk.

The family’s tan-coloured baked mud house was identical to all the others in their alley. The house was already too hot to sleep inside at night, even though the goddess Geshtinanna had only recently returned from her underground confinement bringing the land back to life after winter.

Enki crept quietly past his parents as they snored faintly and stirred on their reed mat bed. From the roof, he could see the morning rim of light striking deep blood orange in the east above the endless plain of the Mesopotamian delta. It was the colour of the embers in the clay oven where his mother baked bread. The air of the plain was not yet wavering and rippling under the baking heat of the day.

There was something about an open plain with no mountains rising in the distance. It was a big sky, an unending sky. The land was already alive with the calls of birds; eagles, crows, doves, calling in a new day above the irrigated pastures and sleepy stirring palms.

He descended the stairs of their house into the open-air kitchen on the ground floor, put some of last night’s leftovers into his satchel, and headed out through the ramshackle east gate onto the plains.

The guard on the east gate was asleep and looked like he had been for a while. The long hollow straw that had been used for last night’s beer drinking at his Deme meeting still hanging from his tunic.

Once outside the city gate, he walked along an irrigation canal leading out of the city into the emerging light of early morning, he felt the cooler air above the canals around his dusty ankles as he progressed towards the farm.

Around him were green fields of grain, date palms and the vegetable plots of Sumerian paradise. The land was ribboned with canals reflecting the deep red of the early morning rays. The fields, a dark plum purple.

It was a breathtaking sight. The inventions of flint spears and animal skin houses were nothing compared to the irrigated plains of Uruk.

The people of Uruk wore clothes made by the weavers in the town. They made Pottery, built houses and, most importantly, grew enough food for everyone to eat. No one went hungry. Such were the gifts of Anu and Inanna, the City’s Gods.

As he walked, Enki kept one eye out for danger. The hill people were rare in these parts, usually only driven by hunger and thirst onto the plains. The city had its own hunters too, so lions and wild beasts were seldom encountered.

This had been a good year for the city. In his mind were the words of his mother reminding him that the good fortune of Uruk was not the same as those outside the city walls.

Uruk’s Gods protected the people of the city.

Hill people had no god to look after them. They were on their own. The hill people had animal spirits, unpredictable, untamed and restless, not to be trusted.

After following the irrigation canal for a while, Enki turned onto a levee recently reconstructed and buttressed after the damages caused by last year’s flood.

Eventually he reached the familiar baked mud brick that bore his family’s seal marking the start of their land.

Enki’s family grew Barley in their main fields, a series of long straight plots of land flowing gently downhill from the main canal making it easy for two oxen to pull the new invention of the plough. In one section grew vegetables: leeks, cucumbers, garlic and coriander. In times of flood, this land was used to quickly carry away the swirling flood waters of spring.

Along their main irrigation stream, a line of Date Palms had been planted. Last year, after a wait of five years they began to fruit. In early spring, the priests would carry out the ceremony of date palm fertilisation marking the start of the growing season.

A week after the ceremony, almost as if on cue, the rivers would rise, swollen by the snow melt of mountains far away. The flood water burst the banks of the Euphrates and blanketed the land to irrigate the waiting furrowed soil.

There was no stopping the flood.

The skill was in managing it.

The city’s engineers knew to drain the soil quickly to avoid the locusts and diseases that accompanied stagnating water.

Quick drainage of the land kept salt levels down. They prepared dams to trap water for the rest of the growing season, levees and irrigation canals to drain the rest.

It did not rain often in Sumeria. There would be no city without this water that flooded the land every year and then receded to a steady but stoic flow.

The use of this hard-won water that gave the fields life was judiciously allocated by the City Council of Elders. They gave land to the capable and took it away from those who squandered it.

Water was also tightly controlled. Enki’s family had been given from dawn until noon every second day to use their share.

He went first to the small sluice gate leading to their allotment and opened it up, using a wooden lever and some effort, straining in the morning light. The water began to flow. He walked quickly ahead using a shovel to open up the channels leading to the barley fields as his father had shown him. As the sun rose, he watched the water slowly soak the trenches he had helped dig.

He moved down to the vegetables and herbs and checked the levels of the water slowly filling the furrows. Cucumbers flowered, leeks grew, garlic browned readying for harvest. Everything was green and verdant promising a bountiful harvest.

Satisfied, he moved down to the animals now to spread out the feed that had been stockpiled from the previous harvest.

When he had finished his main work, he sat in the shade of the animal’s hut and looked out across the plain. He saw the other farmers going about the same work, some working quickly in the cool of the morning, some toiling with plough and oxen.

He dozed.

A hand shook him awake. His father, Sagar. He opened his eyes, blinked a few times then stood next to his father. They looked out on the land.

‘Enki, you have done well, my son’, his father said. ‘All is good and the water is flowing well. We will go and change the drainage to the lower fields in a little while.’

‘Thank you, Father,’ he said. ‘I didn’t think you were coming here today.’

‘That is true. I have been working with the others on the new sluice gate. But I forgot that we had the Temple Official coming and I want to make sure he records the details of our farm correctly. Many of my friends say to be very careful when this new man comes. His parents are hill people, and my friends do not know him very well. Until we know what he is like, we will watch carefully.’

‘Anyway, I have brought a fresh loaf of bread from your mother and still have some salt left over down by the second gate. Let us go and pick some coriander and cucumber and eat.’

They sat down by the flowing channel and ate. Enki asked about the animals, how the seeds for the next season were selected and stored and what it was like when the water did not come in spring. His father answered with what he knew.

‘We are farmers, my son. We do our best and leave the rest to the gods.’ He looked around, gazing into the growing heat of the plain.

Enki’s dad saw that his son was still too young to be able to accept things as they were. At the same time, Enki was seeing his father as too old to seek change. Here was the dream of the father and the son from Uruk onwards through the millennia. The younger generation creating, innovating, pushing for change. The fathers’ time receding, their world growing smaller, watching the new generation forge ahead.

They were waiting for their visitor in any case. They could talk some more until then.

‘Enki, what do you remember about Anu and Inanna from your Sunday lessons at the Temple?’ asked his father.

Enki didn’t think about his reply. It was automatic.

‘Our people were put on the earth to serve the gods. The gods made us out of clay and the blood of a slain god. They breathed life into our bodies. Adappa was the first man.’

Sagar smiled, ‘Yes. What else?’

Again, Enki recited, ‘The creator, Anu, shines down on us from the heavens. He reveals to us his secret knowledge of how to farm the land, the Potter’s wheel and the weaving loom. He conceals in his hands the inventions he has not yet shown us. When Anu judges we are ready, he will reveal these inventions too.’

‘Inanna gives us our families and brings new life into the world. As long as we live by her way and do not displease her, we will live well.’

It occurred to Sagar that Enki was not even thinking. Rote learning did not require thought.

But Enki was thinking.

‘Father, it’s never occurred to me before. Why do we only have two gods living in our city?’

Sagar didn’t really know either. Still, he wanted Enki to stretch his mind further.

He looked up to the sky.

‘Look up there my son. Anu sits on high on the throne of the heavens. The stars that swirl in the deep blue night are his divine cape that disguises his true self. His dreams create the passing of the seasons. His thoughts create the heaven and the earth which live inside of his dream of existence.’

He looked over at Enki. Something was registering. He looked interested.

Sagar admitted, ‘I’m not sure I know what that means.’

Enki didn’t either but it was the most interesting thing he’d ever heard.

A figure was approaching from the distance. Neither of them noticed.

His father continued.

‘Inanna is his daughter. She is a mystery within a mystery. An unending riddle without a question or an answer. Inanna’s dream creates the cycle of life. She watches from the heaven above and chooses which women to bless with children. She is vengeful and easily displeased. Follow her path or risk her taking your children from you, or even worse make a woman’s womb barren.’

Sagar stopped. He felt the tears beginning. He and his wife had been blessed with Enki, but they had lost other children over the years. The sadness so often felt was returning.

Silence again.

Then Sagar realised he hadn’t answered the question. Enki was still waiting.

‘Honestly Enki? I do not think having other gods in our city would be good for us.’

‘Too many and they would fight amongst each other in the heavens above and quibble over our offerings. And the responsibilities we would have to honour them all would be hard to bear. Uruk is blessed to have these two gods. The inventions of Anu grow our city. The way of Inanna nurtures our families who prosper under Anu’s benevolence.’

‘The success of our city is because these two gods work in perfect harmony together. That is what I truly believe. The other cities in Sumeria do not prosper as Uruk does. They have weaker gods.’

Sagar felt a wave of satisfaction. His son was almost a man. Conversation was difficult now. Enki was far smarter than him, but he still had something to offer. They had connected. Now father and son sat motionless watching the fields.

The sounds of the day returned to their ears.

The approaching visitor was close enough now for Enki’s father to notice. His clothes were those of a Temple official and his satchel had a heavy load. They could see now that he was not a Sumerian. His hair was brown, not black like theirs. His eyes less rounded than theirs. His appearance was an unfamiliar sight, slowly becoming more common in Uruk.

Father and Son rose to greet him.

‘Praise to the gods,’ said Tergal in perfect Sumerian as he walked up and raised his hand to the sky. Sagar did the same.

‘Your farm is doing well, Sagar.’

‘We work hard and pray to the gods to thank them for our good fortune,’ he answered.

‘That is good. They are indeed smiling on you,’ said the official looking around.

His voice became less formal and softer, ‘I have four farms to assess today so if we could start, I would be very grateful.’

‘Of course, please follow me,’ said Sagar and the two walked off towards the Barley fields, Enki watching them with interest as they went.

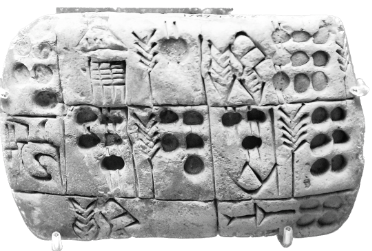

When they returned, they went to the animal hut. Enki noticed the official making hand-marks with a reed on a palm sized piece of clay he had brought with him. Enki had never seen this before.

Tergal wrote for a few minutes and then prepared to leave. As he was putting his work away Enki interrupted, his curiosity could not be contained.

‘Official, what have you been doing, making marks with your piece of clay?’ he blurted out.

His Father intervened, ‘That is not our business,’ he said, looking sternly at Enki.

‘That is all right,’ said Tergal.

‘This is another gift from the Anunnaki and I am happy to show you. Come closer.’

Enki moved in and the Official went down on one knee.

Proto Cuneiform – Courtesy Wiki Commons

‘You see these marks here?’ he said.

‘There are three marks on this side and that means the number three. Now what do you have three of?’ he asked.

‘Oxen,’ replied Enki, excited to be able to answer.

‘Yes,’ said Tergal. ‘And this mark here says exactly that. It is the mark for Oxen. And this line is for sheep and this is for goats. Up here I have written down the number of bushels of Barley you should be harvesting later on. So, in this way, we have recorded what your farm has. It will be used to calculate what share of your harvest will go to the workers in the city and what share will go to the Temple.’

‘Do not ask any more questions,’ said his father. ‘The official is a busy man.’

Enki chanced one last question: ‘But what else can you mark with your reed on that clay other than numbers and things?’

‘That is all that we need to mark down,’ said the official, looking puzzled.

There was nothing else to say. The official thanked Enki’s father and started his walk to the next farm. They watched him go.

As Sagar watched him leave he said, ‘Tergal seems a kind man. I will tell my friends. I don’t think this man will cheat us.’

Then he turned to Enki

‘Enki, you do not need to know the things you just asked.’

‘We live by the hand of our gods. They are great gods and we will live well and enjoy our lives under their watchful eye. Anything higher than that is the concern of our city priests.’

Seeing that Enki had a look in his eyes he had not noticed before, he said:

‘By the way Enki, tonight the irrigation engineers and workers are gathering. Ashur, the high priest of Anu will be opening the new works we have just completed. It is a new type of sluice gate that will divert silt from the canals. Would you like to come with me?’

Enki’s eyes lit up and the subject of the official was quickly forgotten.

You must be logged in to post a comment.